The old saying goes, ‘When life gives you lemons, make lemonade.’ But at the height of the worst recession in nearly a hundred years, a young Benoit Azagoh-Kouadio couldn’t even get lemons. So he started growing them, so to speak.

Benoit had dreamed of becoming a psychedelic researcher before graduating from college with a psychology degree in 2010. He had some transformative experiences with psychedelics as an undergraduate, which is also when he first learned of groups like MAPS and their studies on drugs like MDMA for mental health treatment.

But in the aftermath of the Great Recession and a bleak jobs market, he did what any other sensible person would do: he moved back in with his parents in Vermont.

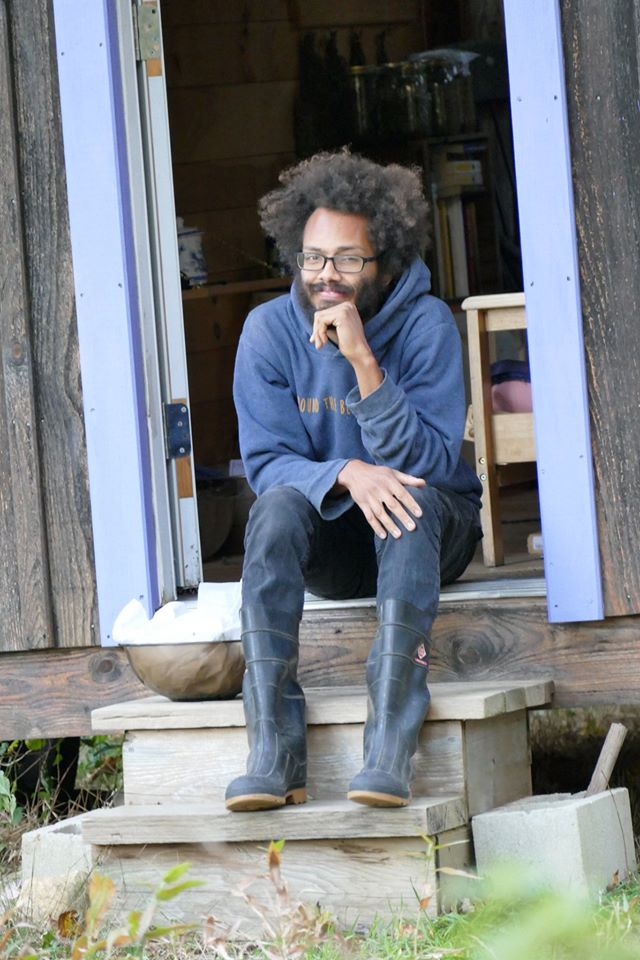

“It was a very bad time,” he recalled to Psychedelic Times. “I was unemployed for a long time, and I had to figure out something to do to keep myself sane. That was when I found gardening, which let me produce good quality food to help support my family.”

What started as a search for cheaper and healthier food turned into a life calling that took him 5,000 miles to Malta and back to New England, where he now lives and works on a farm. In doing so, Benoit re-discovered psychedelic wisdom.

He is now Garden Manager for the Round the Bend Farm (about 30 miles outside Providence, Rhode Island), which focuses on sustainable and permacultural techniques. He describes a ‘closed loop’ system where the farm reuses waste, and even collects from its neighbors waste like clam shells, fish guts, woodchips, animal bedding, manure, and leaves.

“The farm is the perfect place to see the interdependence of our existence,” said Benoit. “What we may think of as ‘waste’ actually gets composted and forms the nutritional basis for the next generation of life. What we associate with death or the end is really just the beginning, which is a very psychedelic principle.”

But just when he thought he was out… he was pulled back in.

Even through his marriage with agriculture, Benoit still lusted for knowledge and action around psychedelics. In 2016 he traveled to New York for the Horizons psychedelic science conference, the biggest event in the business. Luckily, he was able to volunteer and attend for free. He was blown away by the welcoming, eclectic community of researchers, therapists, and advocates.

Even more so, he was inspired by befriending other young people of color like Ismail Ali, an attorney for MAPS, and Oriana Mayorga, who helped operate the Horizons event. In fact, Benoit was initially motivated to attend after realizing that the only depictions of psychedelic researchers he saw in the media and from groups like MAPS were of white people.

He was encouraged that other people were also thinking critically about lack of diversity and representation in the space. Since then, he has become more involved in various psychedelic advocacy efforts, including helping to organize and host events back in Massachusetts with the Boston Entheogenic Network (BEN).

“I’m trying to ask harder questions, not just about the role of people of color in this movement, but about how these medicines will serve communities of color,” he said. “Our communities by and large aren’t familiar with psychedelics and don’t have many notions for what they are capable of.”

Benoit encourages young people of color to do more psychedelic education and outreach in their own communities, especially through professions like mental healthcare and social work. Churches are also good targets, because they serve important psychological and spiritual needs in these communities.

And farming plays a key part too. While mainstream psychedelic research and policy reforms are focused on clinical psychedelic therapy or commercial dispensaries, Benoit urges people to grow their own medicines—whether that be cannabis, psilocybin mushrooms, or other substances.

“I’m a big proponent of the herbal medicine model,” Benoit said. “It gives you a deeper appreciation for the medicine because you see it as not just something you take, but something you have an intimate relationship with, where you’re involved in caring for it.”

Of course, that is the same impulse that animates movements like Decriminalize Denver and Decriminalize Nature Oakland, both of which made history last year by decriminalizing personal possession and cultivation of various naturally-occurring psychedelics.

After spending ten years working on a farm, the younger Benoit’s dream of being a psychedelic psychotherapist has sprouted into something much greater: he hopes to open a psychedelic clinic on a farm, where people can trip in the comfort and safety of nature. And if they choose, they can get their hands dirty and their brows sweaty.

“Having the farm as the backdrop for your psychedelic experience can be very nourishing,” he said. “Farming work both demands and rewards the entirety of your being. Body, mind, spirit—it’s all connected in the act of farming.”