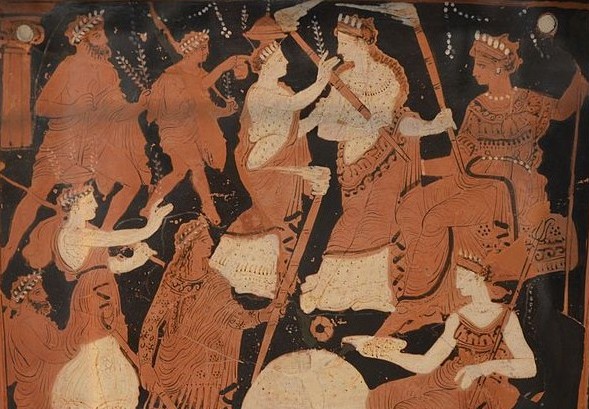

Certain archetypes commonly appear in ayahuasca visions. Image Source: Flickr CC User Apollo.

If you’re curious about ayahuasca visions, Benny Shanon is a name you should know. Shanon is a professor of psychology and ayahuasca researcher best known for his theory that entheogens fueled ancient societies’ search for spirituality and his research on the psychology of ayahuasca. He is also one of the first researchers to attempt to scientifically explain the often universal archetypes found in ayahuasca visions and how they contribute to personal healing.

In a comparison study published in a 1997 MAPS newsletter, Shanon made  a list of the most common archetypes he encountered in his seventy plus ayahuasca experiences as well as the visions of nineteen research participants. The lists between the two groups were similar—both sets of data included visions of animals, otherworldly beings, cities, palaces, birds, felines, serpents, divine beings, landscapes, human beings, and forests, and these visions often held similar ranks in the list as to how often they appeared.

a list of the most common archetypes he encountered in his seventy plus ayahuasca experiences as well as the visions of nineteen research participants. The lists between the two groups were similar—both sets of data included visions of animals, otherworldly beings, cities, palaces, birds, felines, serpents, divine beings, landscapes, human beings, and forests, and these visions often held similar ranks in the list as to how often they appeared.

Below I’ve cataloged some of the major archetypes found in ayahuasca visions that Shanon and others describe, supplemented with examples from my own experiences, descriptions from friends, and stories found in studies to show how people intuit personal meaning from these universal archetypes. This is by no means an exhaustive list, and it doesn’t account for the deep emotions, bodily sensations, and insights that often accompany ayahuasca visions (or that exist without any visions at all). But it does provide important hints about how ayahuasca provides healing for some of the most difficult-to-treat illnesses of our time.

Jungle Fauna and Flora

One of the most famous archetypes of ayahuasca visions is Amazonian fauna and flora, including serpents, jungle cats, monkeys, and rainforest plants. Sometimes you interact with the animal or plant spirit, and sometimes it is simply a lingering, solitary image.

Shanon’s research suggests these jungle visions are one of the most common, and I can attest to this in my own ayahuasca visions—I’ve seen jaguars and marmoset monkeys blinking at me behind closed eyes, motioning for me to follow them. This archetype might be represented in conjunction with others found on Shanon’s list, like one woman’s vision of “a young girl made of green plants. I had a whole conversation with her in a language that I don’t know. Behind her were dozens of plant-people watching and participating.”

Why would that be? Some people chalk it up to the power of suggestion—if you go into your experience knowing that Amazonian flora and fauna are common visions, then you will see them. But my own experience negates that idea: I went into my ceremony with little preconception of what an experience might be like or how to prepare for it, and still I had visions of jungle animals. Even when taking ayahuasca outside of South America, people have visions like these. A shaman would explain this phenomenon in a different way: taking ayahuasca puts you in direct communication with the spirits of the plants found in the ayahuasca brew. Because these plant spirits impart their wisdom, it makes sense that the visual imagery would be of their own environment.

Palaces and Cities

Another common theme is of gilded palaces, ancient cities and civilizations, and celestial beings in majestic environments. Just as it’s curious that a person taking ayahuasca outside of the Amazon would see jungle flora and fauna, Shanon notes that indigenous people who’ve never left the Amazon also see “magnificent palaces—items which are definitely not part of the Amazonian or South American milieu.”

One friend of mine, Gary, described a “huge, organic, intricate, complex gate” that appeared in his initial visions. While this image was awe-inspiring, people’s visions of palaces or cities can range from the celestial to the macabre. Gary shared another vision that related to his girlfriend at the time, this one much darker but full of meaning:

“I saw a castle that was oozing out black ooze from the windows of the castle. I knew instinctively that this castle was representative of my [hometown social scene], being around a lot of people with psychic baggage, a lot of alcoholics, a lot of people with serious addiction issues. I remember trying to reach into the castle to grab [my girlfriend] and take her out of it. But when I would put my hand in the castle to get her out, the ooze would crawl up my arm and engulf me.”

Gary felt this image was a good representation of what was happening in their relationship at the time: “I couldn’t save her from the world she’d chosen to be connected to. And the more that I did try to, the more I was getting roped into that world.”

Mother Ayahuasca

People often refer to ayahuasca as Mother Ayahuasca because of the feminine, nurturing spirit they encounter in ceremonies. My friend Margaret described a vision that epitomized this sense of ancient feminine wisdom, or the Divine Feminine, for her—she saw herself fall in love, marry, become pregnant, raise five children together, grow old, and die together. She said, “I felt what it was like to give birth to children, and in other visions, giving birth to myself. I gained a greater sense of femininity and what it means to be a woman and to be human.”

Ayahuasca also often comes to people in the form of a giant snake. Lara Charlotte of the Garden of Peace Ayahuasca and Master Plant Healing Center explains her own experience with this feminine energy: “For me, she’s perceived as a huge green and black boa constrictor that’s wrapping around my body and through my body, dancing with me and dialoguing with me.”

Anima Mundi, or the “Web of Interconnectivity”

One of the most interesting visions is what Shanon describes as the “web of interconnectivity,” a universal spirit to which we are all connected. Shanon describes the web as “translucent strings, like the threads of a spider web, that tie everything which is seen under the intoxication with open eyes.” Many of his research participants described something similar, and one woman said the most important lesson she got from her ayahuasca experience was that “the Divine does indeed exist.” When asked how she came to that conclusion, she described a “translucent web that interlinks everything and sustains all of existence.”

Shanon also notes that this is often present in ayahuasca experiences, even without visual representation. Many of his research participants described insights that share an uncanny resemblance to Plato’s idea of anima mundi, which means “world soul” in Latin—the concept that there’s an inherent connection between all living things on earth.

Finding Personal Meaning

Shanon notes that while ayahuasca visions often cater to archetypes, the meanings are very personal. Visions usually carry a message that relates to your life or something you’re struggling with—like long-held trauma, vices or relationships that no longer serve you, or gender identity.

But outside of the personal, perhaps the most important message is the one of Plato’s anima mundi, the web of interconnectivity. In a distracted, fast-paced world rife with technological advances that often isolate us rather than connect us, many people could use a reassuring reminder that we are all connected. Deep-seated, existential fears of being alone in the universe often lie at the root of many of society’s illnesses, like anxiety and depression, which have skyrocketed in the last century. Without rallying to effectively treat these problems, we may be on a collision course for more mental and emotional anguish—but perhaps a vision of something different can turn us around.