Emanuel Sferios founded DanceSafe in the San Francisco Bay Area in 1998, but the nonprofit quickly grew into a national organization with chapters across North America. | Image Source: DanceSafe

Imagine walking into a music festival and being greeted by someone saying, “Welcome to the party, would you like your drugs tested to make sure they are safe?” It might sound crazy to some—or too good to be true to others—but organizations are working towards this in Europe and the US. Not only are they legal, they operate with the blessing (and sometimes even the funding) of local government and law enforcement.

Emanuel Sferios is the founder of one such advocacy organization called DanceSafe. In the first part of this two-part interview, Emanuel shares the story behind the origins of DanceSafe and explains why harm reduction services like the kind DanceSafe provides are so critically important in bringing responsibility and real talk into environments where recreational drugs are being used. In a day and age where the “molly” or “MDMA” that someone gets could actually be bath salts, organizations like DanceSafe are literally saving lives. Today, we talk to Emanuel about why he started DanseSafe, why he foresees major changes in drug policy coming up in the near future, and how prohibition creates a dangerous situation for people who choose to use MDMA. Next week, Emanuel talks to us about the inspiration and hopes for his upcoming feature-length documentary MDMA: The Movie.

Thank you for speaking with us, Emanuel. Can you tell us about what prompted you to found DanceSafe?

I started DanceSafe in 1998 after a friend gave me a few ecstasy tablets. I hadn’t taken MDMA in over a decade, and I got online to see what we had learned about the drug in all this time. I learned that the market was highly adulterated and that people were dying after consuming fake tablets containing Para-methoxy-amphetamine (PMA). I also learned that the Dutch government was funding pill testing programs for users where they would set up booths at raves and test ecstasy tablets using a chemical reagent in order to help users avoid the fake and more dangerous pills. Essentially, I said to myself, “I’m going to do this here.”

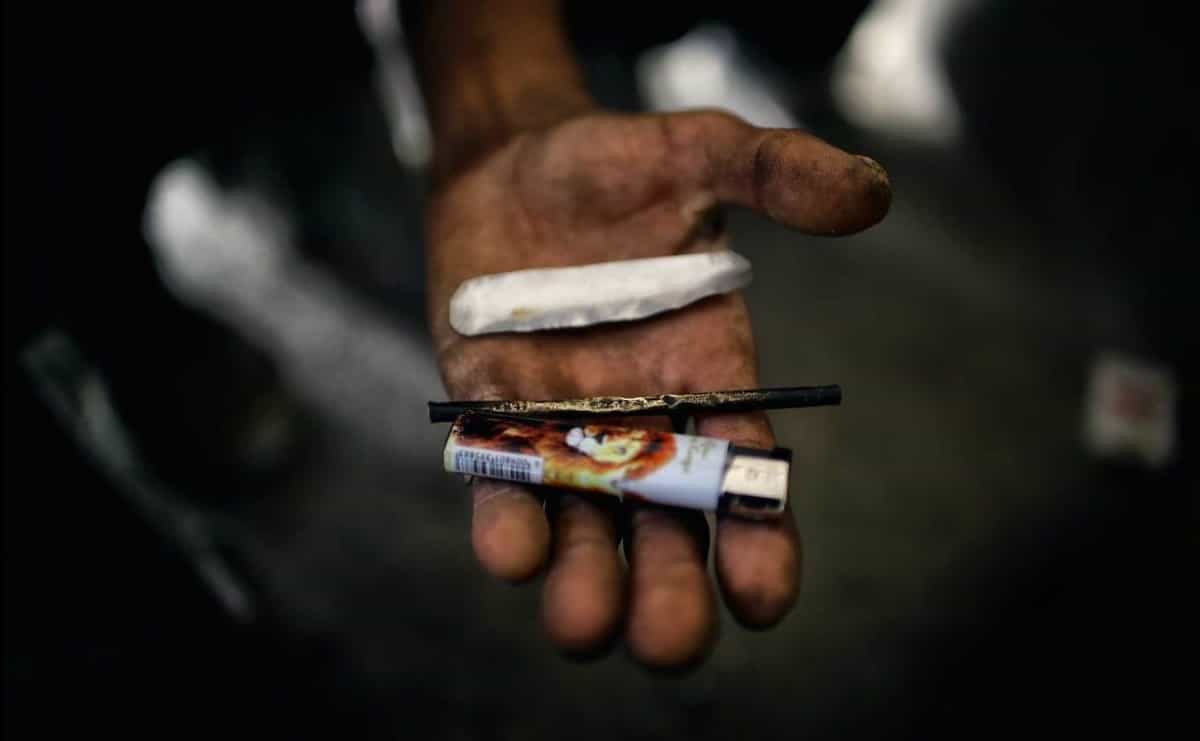

I had never actually been to a rave prior to starting DanceSafe, and truth be told, I didn’t realize how much misuse and abuse of drugs was actually taking place within the dance music community. I pretty much assumed that the only problem was fake and adulterated ecstasy pills. The first real teaching moment I had was watching a young woman—clearly high on something—walk around a party with a little bottle of white powder and a tiny spoon offering “bumps of K” to everyone around her. I saw teenagers lean over and snort a mystery powder off a spoon from a total stranger, and it was [at] that point [that] I realized DanceSafe needed to become something much more than just pill testing. So I began researching and designing a peer-education program with the goal of training young people to be harm reduction counselors, or peer-educators, within their communities. The idea was to provide non-judgmental, safer drug use information, or how I sometimes describe it… to create a responsible drug using culture. Of course, the culture was and is about much more than psychedelic drugs, and DanceSafe quickly became about health and safety in all aspects, including safe sex, hearing protection, getting home safely, consent and women’s issues. Within six months, we expanded from a chapter in Oakland to 25 chapters around the US and Canada.

What sort of impact have you seen DanceSafe have on the culture of music festivals and raves?

I think DanceSafe has had a tremendous impact on the culture, and I’m very proud of all the volunteers and staff who have kept the organization alive for all these years. DanceSafe was the second entity in the world—after the Dutch Government—to provide onsite, public pill testing services, and now these services are offered in every industrialized country in the world, many with the support and funding of their respective governments. The media and public health departments are also much more supportive of harm reduction today and much more educated around MDMA (with less hysteria) than back in the late 90s. A lot of this is because the same young people who were raving and utilizing DanceSafe’s services then are now in positions of power within the media and public health. So culture is changing. It may feel slow to a lot of people, but if you look at recent gains in marijuana reform, you can see how things can change rather quickly too. I foresee major changes in drug policy coming up in the near future.

At the same time, I must qualify these positive changes with the impact prohibition continues to have on the markets. Despite cultural progress, the situation today is much more dangerous than it was back when I started DanceSafe, and this is largely a result of the influx of cathinones on the MDMA market. The cathinone class of drugs (aka “bath salts”) are masquerading as MDMA and changing the culture in negative ways. Use patterns around these new stimulants more resemble that of cocaine than a psychedelic. People are snorting large amounts, redosing throughout the night, and generally taking “Molly” in ways they never used to—because most of what is sold as Molly today is not MDMA but methylone or other bath salts. The worst part about this is that most people don’t know they aren’t taking MDMA. To them it’s all just “Molly” and they think that means “pure MDMA.” So the culture has developed these dosing patterns for methylone, but they think it’s MDMA, which makes it quite dangerous when real MDMA comes along. This confusion I believe is responsible for the increase in MDMA-related fatalities recently. Prohibition is still creating a very dangerous situation.

Some festivals like Boom in Portugal go so far as to offer on-site drug testing so that festival-goers can be sure of what substances they are taking. Do you think this is something that should adopted at music festivals worldwide, and if so, why?

Of course! It’s easy to do pill testing in Portugal because they have decriminalized drug possession, and there’s no risk of arrest. Decriminalization is a great first step towards the more important harm reduction goal of legalization and regulation. Legalization is, in fact, a harm reduction goal, perhaps even more so than it is a civil rights goal because prohibition is actually the abdication of drug control. It simply turns over manufacture and distribution of drugs to criminals, which creates an adulterated market where users have no idea what they’re taking nor how strong it is. Decriminalization, at least, allows testing services like they do in Portugal, so some people could identify the contents and purity (milligrams or whatever) of their drugs. It’s a great first step. Pill testing could also be implemented without broad decriminalization. Police and public health could agree on amnesty stations where users could test their pills. These stations could exist inside festivals, outside in the parking lot, or both. There could also be drug testing centers in health clinics in major cities where users could bring their drugs for testing.

You have advocated for harm reduction approaches in drug policy to lawmakers and police forces. How open are they to this message, and in your eyes, what needs to happen for the tide to start really changing in drug policy on a national level?

I love the model of opening testing centers in health clinics because it avoids involving festival promoters who are afraid to embrace harm reduction services because of the RAVE Act. And truth be told, I’ve found it is easier to get police and city officials behind harm reduction services. Promoters fear federal authorities are going to accuse them of encouraging drug use, but city officials have often went against regressive federal legislation to implement policies that better protect their citizens. Take a look at marijuana reform. This all started on the local and state level. I remember years ago when Berkeley passed an ordinance putting marijuana enforcement on the lowest priority level, even below that of jaywalking. Similarly, I live in a marijuana-growing county in California, where local officials tolerated the industry long before federal authorities started to. Needle exchanges also began at a local level, winning support of local police and city officials. The Feds eventually had to accept it. So we can make changes on a local level, and this can eventually change federal policy. I call it the “trickle up” approach, and it works. It just takes courage and honesty.

To read about Emanuel Sferios’ upcoming feature length documentary MDMA: The Movie, check out the second part of our two-part interview next week.

hello Dance safe, I sort of fell into harm reduction by way of a rather long story but would like to both congratulate & follow Emanuel. Is there a link or web page he hosts to keep me up to date with trends in harm reduction ?