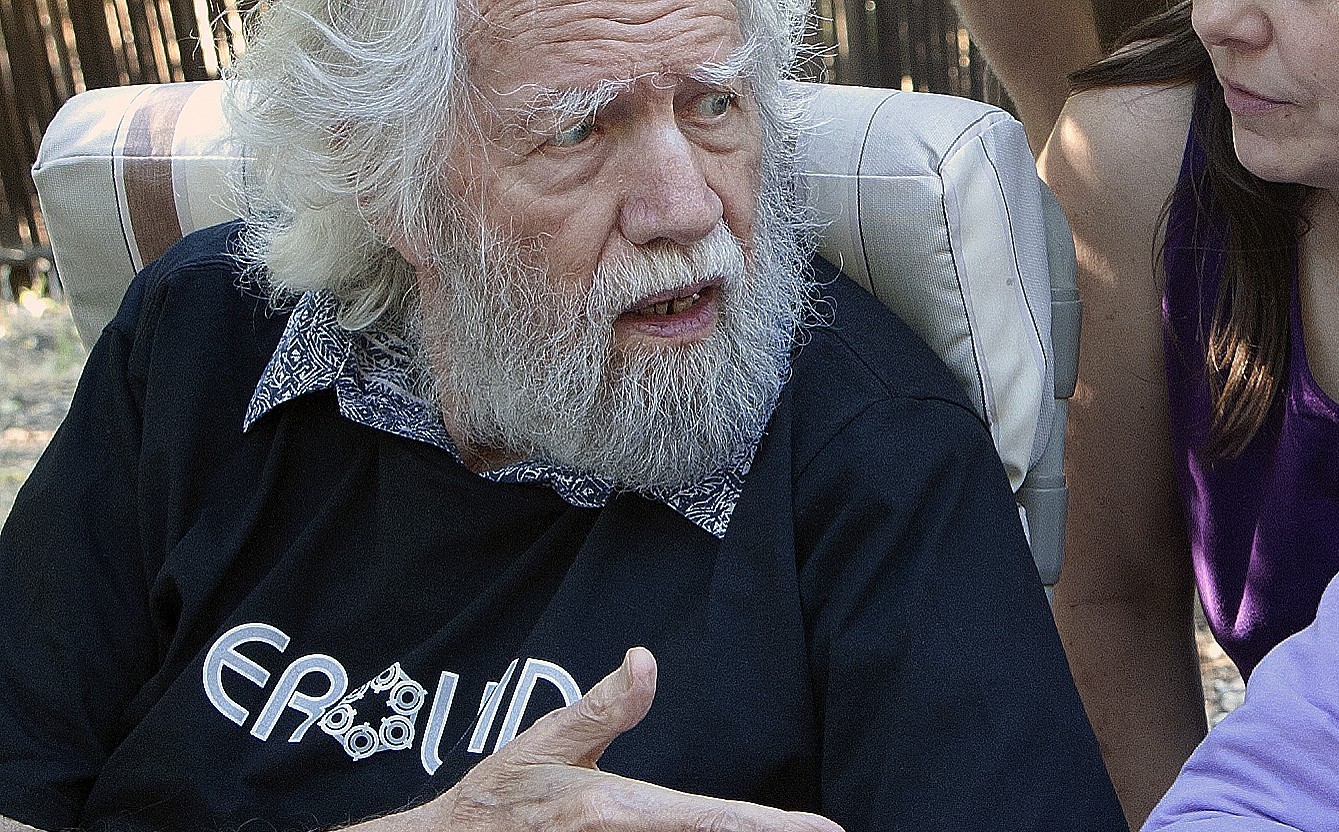

Alex Shulgin (1925 – 2014) helped make MDMA widely known and contributed vastly to the repository of human knowledge of psychedelics | Image Source: Wikimedia Commons user JonRHanna

Alexander Shulgin has a varied reputation, depending on who you ask. Ask a DOW Chemical executive, and they might remember the part he played in making biodegradable pesticides. Ask a DEA officer, they’d remember him as the man who both served as an expert witness for the DEA and was later raided by the same agency. Ask any psychonaut worth their salt, and they’ll tell you he’s the Godfather of Psychedelics, the biochemist and pharmacologist who reintroduced MDMA to the mainstream and designed and synthesized hundreds of psychoactive compounds that he tested on himself.

It’s a hefty biography. But perhaps the most important thing we should know about him is one that many do not: that his creations live on today in the form of cut ecstasy pills and blotters that look like LSD. His creations are not inherently bad, but the misinformation that surrounds them can lead to people use them dangerously (something against which Shulgin himself spoke out against). A closer look into this fascinating man’s life provides a unique perspective on psychedelic substances as well as a message of caution for those who use psychedelic substances today.

Alexander Shulgin worked for DOW Chemical Company in the 60s, patenting a biodegradable pesticide called Zectran. It was at DOW that Shulgin first started synthesizing new psychedelic substances. | Image Source: Wikipedia via user JonRHanna

Shulgin’s Start in Psychedelics

Shulgin’s interest in psychedelics was sparked in the ‘50s after an experience with mescaline made him realize that “that there was a great deal inside [of him].”

Shulgin’s work dealt principally with the detailed manipulation of individual molecules. With his expertise in both chemistry and pharmacology, he could look at, for instance, the DMT molecule and predict what would happen if he added an extra methoxy at a given position. Some of his better-known creations like 2C-B and DOB — both currently listed as illegal Schedule I substances — are still well-known in some circles.

Shulgin consumed his creations, drugs which had never been taken, or even seen, by humans. While his practice fundamentally can’t be called safe, he performed his experiments using an analytical and reasonably responsible process (given the circumstances). Using his extensive knowledge of pharmacology, he made educated guesses about a new drug’s threshold effect. He then took 1/1000th of that dose and minutely increased it until he felt something. He spoke of his experiences with a sense of awe and wonder:

“The most compelling insight of that day was that this awesome recall had been brought about by a fraction of a gram of a white solid, but that in no way whatsoever could it be argued that these memories had been contained within the white solid. Everything I had recognized came from the depths of my memory and my psyche. I understood that our entire universe is contained in the mind and the spirit. We may choose not to find access to it, we may even deny its existence, but it is indeed there inside us, and there are chemicals that can catalyze its availability.”

In the 90s, he detailed the chemistry and his experiences in two books he wrote with his wife Ann. The first, called TIHKAL (“Tryptamines I Have Known and Loved”), details chemicals similar to DMT and psilocybin. His second book PIHKAL (“Phenethylamines I Have Known and Loved”) deals with chemicals similar in structure to mescaline and amphetamine.

The Dangers of DOB and 2C-B

Unscrupulous dealers have been known to pass off Shulgin’s creations as better-known drugs like MDMA (ecstasy) and LSD. Aware of these issues, Shulgin has spoken out against the commercialization of his drugs for profit. “I’m disturbed by the fact that you get someone who wants to make a pile of money and doesn’t give a damn about the safety or the purity,” he said. “It’s a motivation that I’m uncomfortable with. People using psychedelics, I’m not uncomfortable with. I consider it a very personal exploration. But I’m very disturbed by the overpowering of curiosity with greed.”

DOB molecule. | Image Source: Wikimedia Commons via user Harbin

DOB is a Shulgin psychedelic active in small enough quantities to pass as LSD on a blotter. While taking too much LSD can certainly be traumatic, there’s no acute overdose possible. But this isn’t the case for DOB, unfortunately, nor for Shulgin’s other substituted amphetamines. To complicate the issue, DOB’s onset can take 2-3 hours—much longer than LSD. Its long onset can lead users who think they’re taking LSD to believe they haven’t taken enough, then consume too much and become overwhelmed, or worse. An overdose of DOB, like amphetamine, can result in dangerous heart issues.

2C-B molecule. | Image Source: Wikimedia Commons via user Harbin

2C-B is another psychedelic creation, but it’s more like MDMA in its effects (despite the fact that it’s only a single methyl group different from DOB). It takes 30 minutes to 2 hours to take its effect and lasts four to six hours. 2C-B is regularly found in pressed ecstasy pills along with a medley of other substances. This can cause issues for rave-goers who believe they’re taking something entirely different, a problem tackled by harm-reduction organizations like San Francisco-based DanceSafe.

Shulgin’s Complicated Legacy

Shulgin’s creations are truly fascinating and can teach us a great deal. That adding a single atom to a molecule can completely change its activity and effects is stunning. It speaks to the infinite complexity of our minds and neurochemistry. These designer drugs also point to a future of specifically, precisely-designed substances that could give us exactly the shade of experience we are looking for.

But the dangers and ambiguities surrounding substances like 2C-B and DOB also remind us of the necessity of continued psychedelic research. Unlike more established drugs with a long history of natural experimentation and sometimes decades of modern research, we’re still in the process of learning what exactly these new drugs do. While the legacy of his designer drugs lives on in sometimes dangerous ways, the contributions that Alexander Shulgin made to the annals of psychedelic research point us toward an exciting future to understanding the chemistry of psychedelics and how they interact with our brains.