The Mazatec of southern Mexico have used psilocybin mushrooms and sativa for spiritual purposes for generations. | Image Source: Aminus3 User pasquinolin

The Mazatec people are an indigenous tribe that hails from the mountains of Oaxaca, Mexico, best known for their syncretic form of Christianity and indigenous shamanism. In their most sacred rituals, the Mazatec use powerful visionary plants like psilocybin mushrooms and salvia divinorum to commune with spirits, divine information, heal ailments, and have a direct experience with the divine. When Westerners were allowed to participate in these rituals in the early 1950s, it opened a psychedelic Pandora’s box, introducing psilocybin and salvia to the modern world, influencing major players in the psychedelic revolution, and forever changing the landscape of modern man’s relationship to psychedelics.

Seeking the Magic Mushroom in Mexico

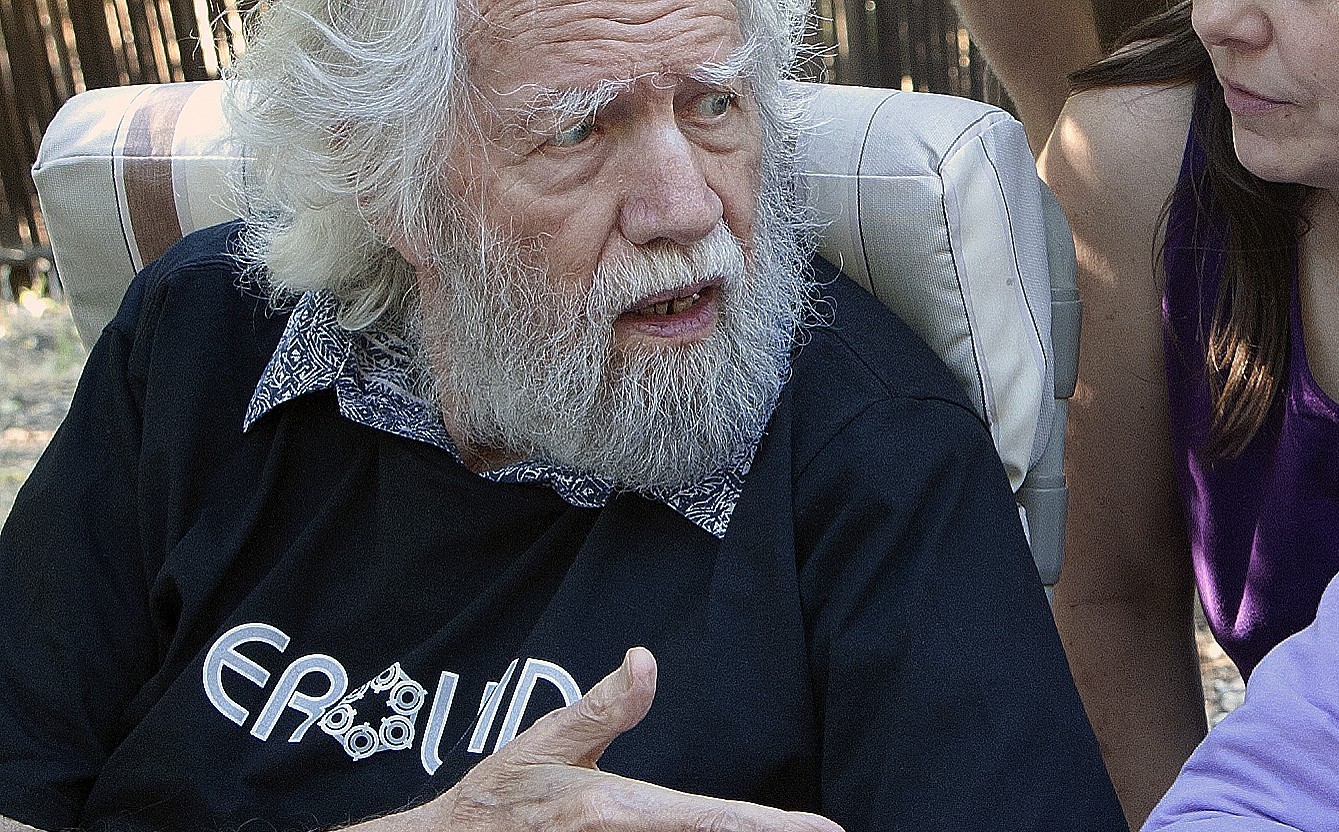

While history suggests that psilocybin was used by cultures dating back thousands of years, the modern world first learned about psilocybin mushrooms thanks to two Americans who traveled to Mexico in the 1950s. Gordon Wasson and Allan Richardson, a banker and a society photographer from New York, first traveled to Oaxaca, Mexico, in June of 1955 in search of a divine mushroom. There they met Maria Sabina, a Mazatec shaman, or curandera, who shared the psilocybin mushroom with them. Thanks to Sabina’s open spirit, Wasson and Richardson became some of the first Westerners to participate in the sacred Mazatec ritual called the velada.

Wasson’s account of their profound experience was published in Life magazine in 1957 in a piece titled “Seeking the Magic Mushroom,” and allegedly went on to inspire Timothy Leary and countless others to seek out the psilocybin mushroom in Mexico. The popularity of the article led to a deluge of hippies, tourists, and celebrities traveling to the Mazatec city of Huautla de Jimenez, including the likes of John Lennon, Mick Jagger, and Bob Dylan.

Maria Sabina became both a hero and an outcast for her role in sharing a guarded Mazatec tradition with outsiders. Within her own community, Sabina was seen as a traitor; vandals burned her hut down, forcing her to move to the outskirts of town. To the rest of the world, Sabina became an unlikely celebrity, and to this day she is seen as an outsider hero throughout much of Mexico as a symbol for the value of indigenous ways and psychedelic experiences.

Wasson maintained friendly relationships with Sabina despite the fallout from his article. He returned to Oaxaca in the 1960s with Albert Hofmann, the Swiss scientist famed for being the first person to synthesize and ingest LSD and the first person to isolate and synthesize psilocybin. With Maria’s help, they were allowed to take part in a ceremony with salvia divinorum. Afterwards they procured full plant specimens for botanical and chemical study, introducing yet another major psychoactive plant to the west.

Wasson also offered Sabina synthetic psilocybin pills on this visit. After journeying with them, Sabina commented that the pills had the same spirit as the mushrooms themselves, verifying the travelers’ hopes that synthesized psilocybin — which is much better suited for research and therapy — could have all the benefits and effects as the mushroom itself.

Pandora’s Box

The introduction of psilocybin and salvia to people outside the Mazatec culture was both revelatory and controversial. The Mazatec faced an unwanted tide of attention from the outside world: some of their most sacred rituals and plants were defiled by outsiders who did not see their visionary plants in the same reverential context as they did. We cannot deny the long-reaching consequences of these discoveries. But equally, we cannot discount the countless people across the world have had meaningful experiences with these plants, nor the scientific research that shows their great promise in treating end-of-life anxiety, easing obsessive compulsive disorder, ending tobacco addiction, treating depression, and reducing inmate recidivism. For better or for the worse, once the genie is out of the bottle, it can never go back. In the spirit of preserving their legacy, let us remember to appreciate the invaluable gifts that the Mazatec people have contributed to psychedelic understanding, and continue to emphasize the responsible and science-backed use of these Mazatec sacraments for healing as they were originally intended.